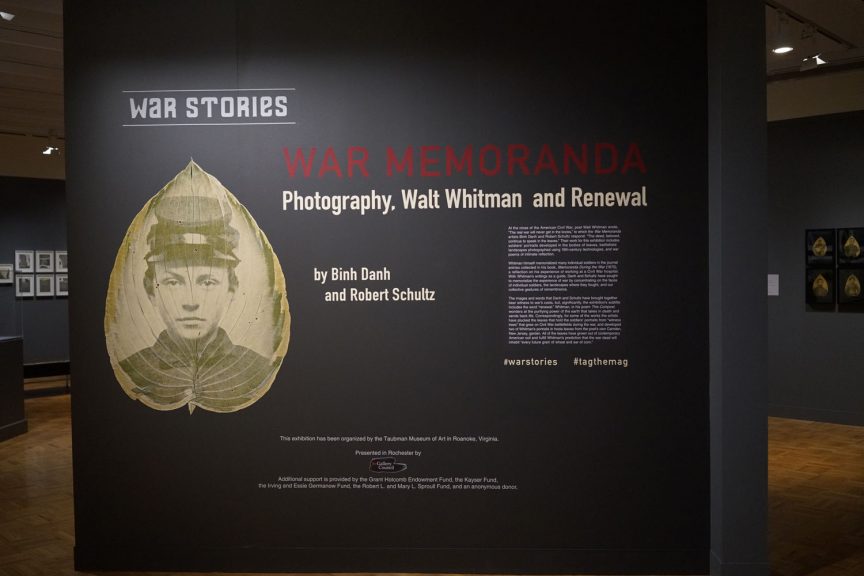

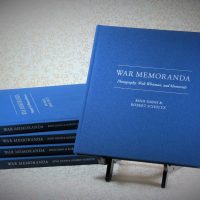

War Memoranda : Photography, Walt Whitman, and Renewal

War memorials are too often mute, naming the dead with fitting solemnity but neglecting to say anything of what the dead know. The cenotaph, the column, the mounted soldier—such monuments stand for the soldierly virtues of courage and sacrifice but say little of how courage differs between men and what exactly each has sacrificed. Perhaps of all our national monuments, only the Vietnam Veterans Memorial gives the civilian a shiver of understanding. "We wade on in", Schultz writes of the Memorial, as if we were not on the Mall in Washington but in the swamps of southeast Asia, a place where "men and women hold each other, mortal, drowning." Faced with Maya Lin’s austere granite gash, "particular deaths rush out". It is impossible not to be moved under such an assault, not to feel in some small but significant way involved.

– Molly Rogers, “Stricken,” author of Delia’s Tears

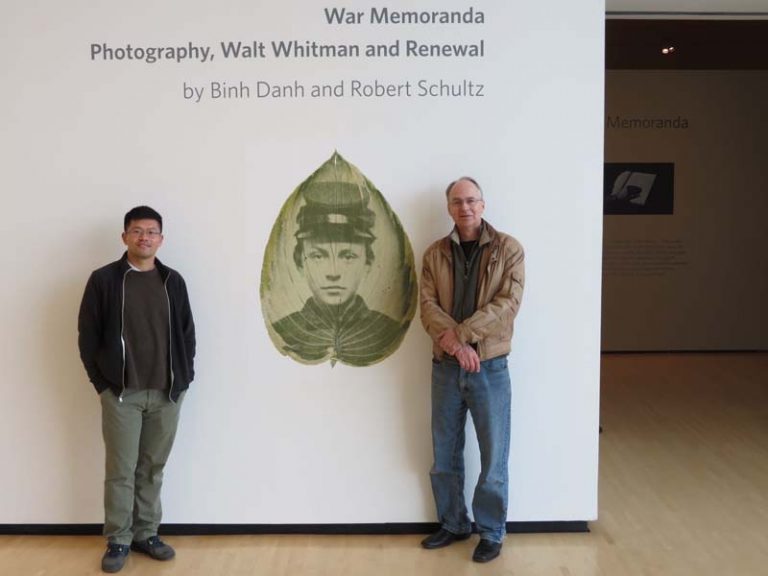

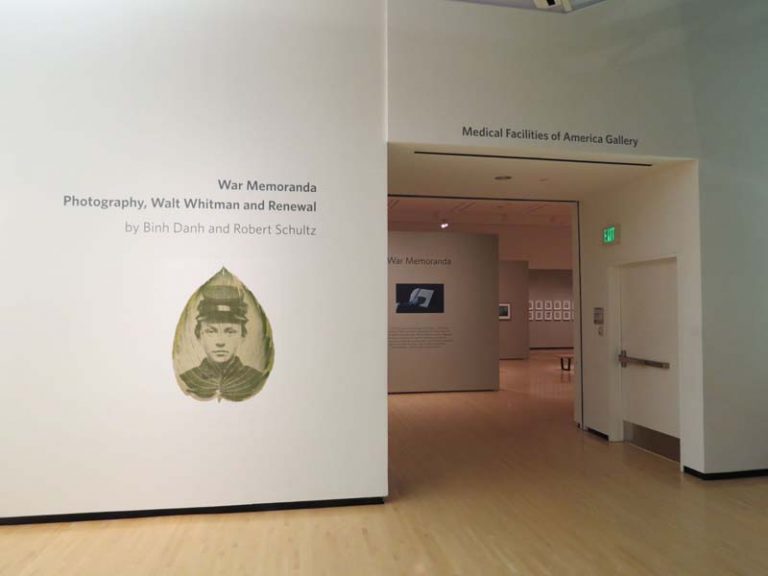

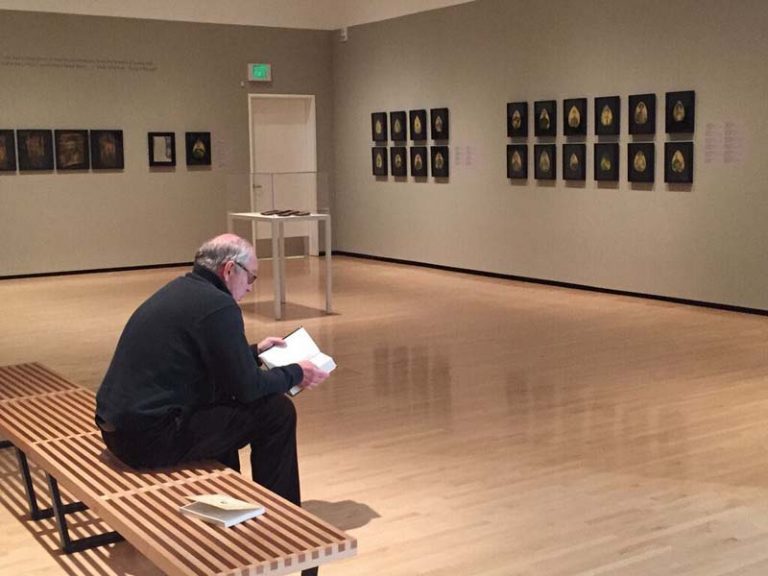

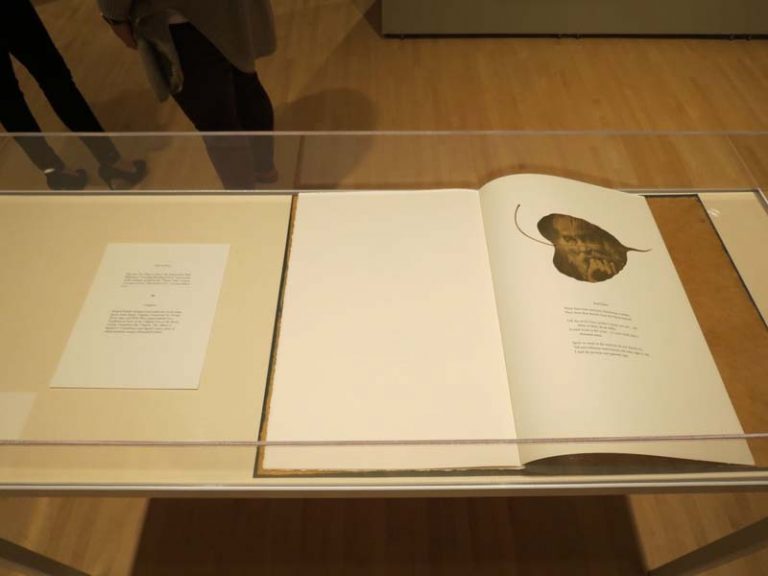

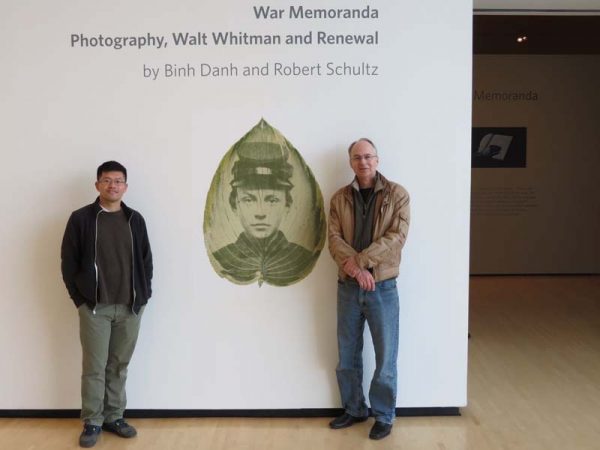

War Memoranda, a word and image exhibition featuring original photography, poetry, leafprints, and artist’s books by Binh Danh and Robert Schultz, draws upon the war poems and prose of Walt Whitman and upon the Liljenquist Collection of Civil War portraits held in the Library of Congress.

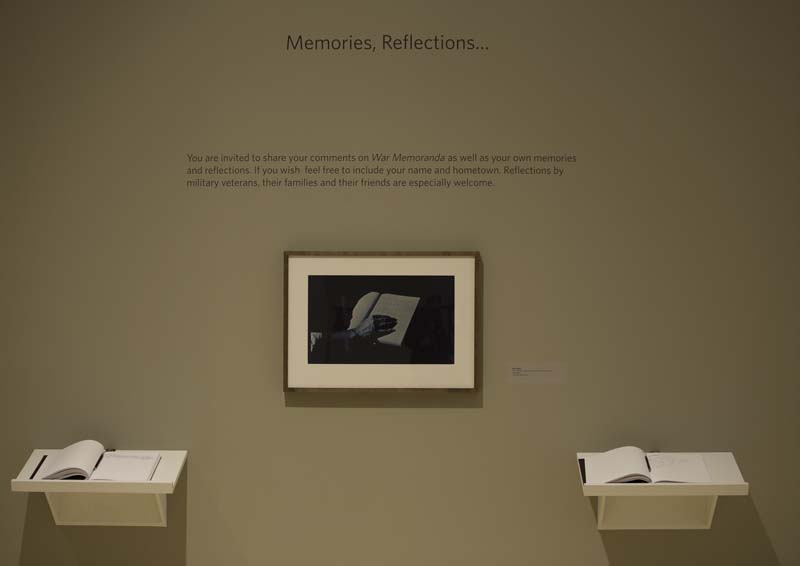

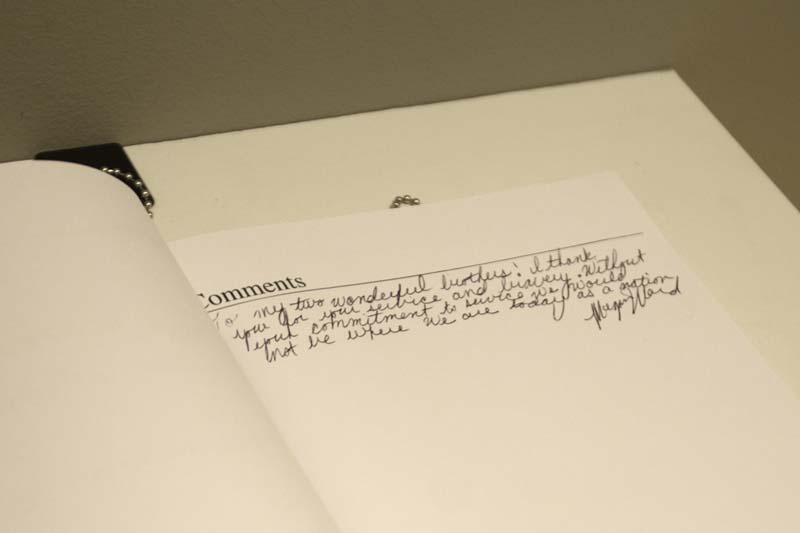

The exhibition ran February-May 2015 at the Taubman Museum of Art, Roanoke, Virginia, occasioned by the 150th anniversary of the surrender agreement signed at Appomattox, Virginia, April 9, 1865; the 150th anniversary of the publication of Walt Whitman’s war poems in Drum Taps and the 160th anniversary of the celebrated first edition of Leaves of Grass, published in 1855. At the same time, the exhibition marked the 50th anniversary of the beginning of the U.S. air campaign “Operation Rolling Thunder” in Vietnam and the introduction of the first official U.S. ground troops into the war (March 1965). War Memoranda next traveled to the Memorial Art Gallery of the University of Rochester in Rochester, New York (August 21 – October 16, 2016) and to the Phillips Museum at Franklin & Marshall College, Lancaster, Pennsylvania (September 4 – December 7, 2018). Information for potential future venues is available from the Taubman Museum of Art.

Full Exhibition Description

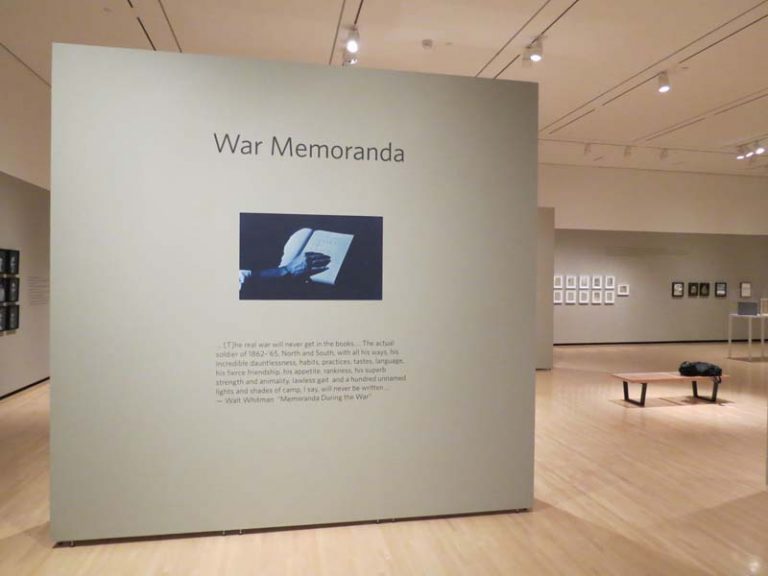

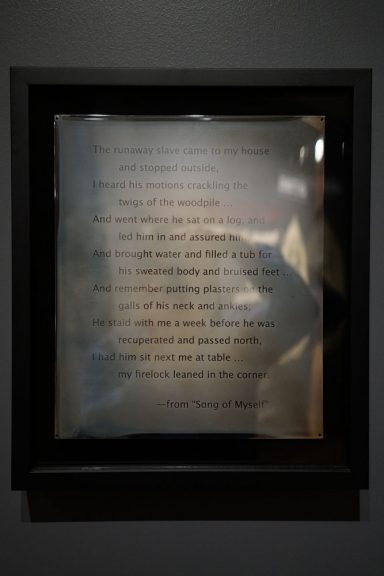

“The real war will never get in the books,” Whitman declared, citing the “interior history” of “the actual soldier of 1862-’65, North and South, with all his ways.” Taking on this challenge, photographer Binh Danh and author Robert Schultz have drawn upon the poetry and notebooks Whitman jotted while tending the sick and wounded in Washington, D.C.’s hospitals and upon the magnificent Liljenquist Family Collection of Civil War portraits held in the Library of Congress. And in a final turn, the collaborators present memorials to their own wars—in Vietnam, Iraq, and Afghanistan—applying the techniques and media employed by Whitman and the great Civil War photographers. Merging past and present, War Memoranda evokes the secret, “interior history” of war.

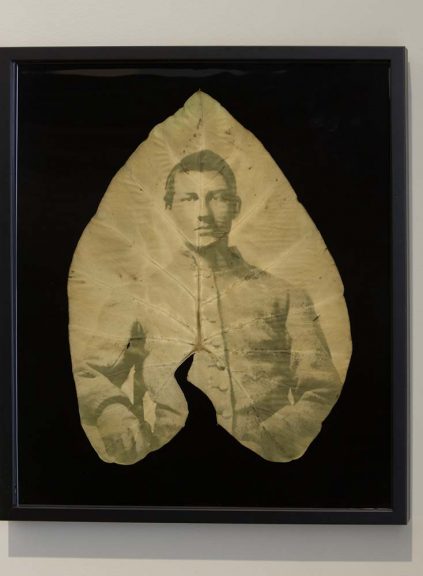

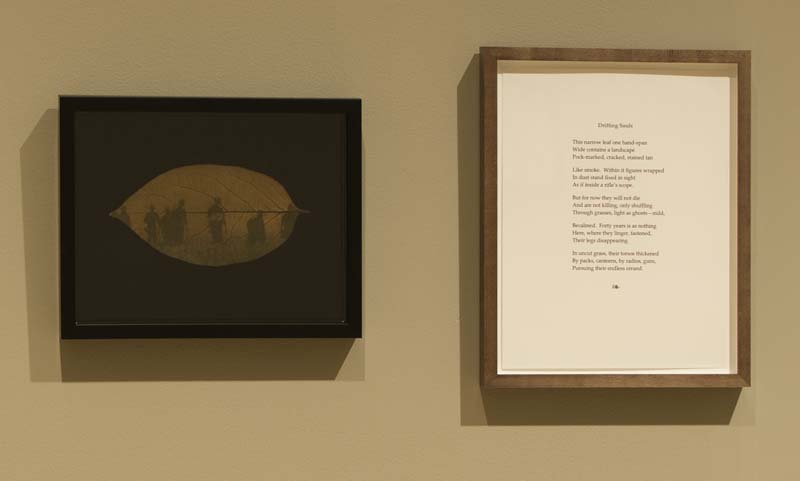

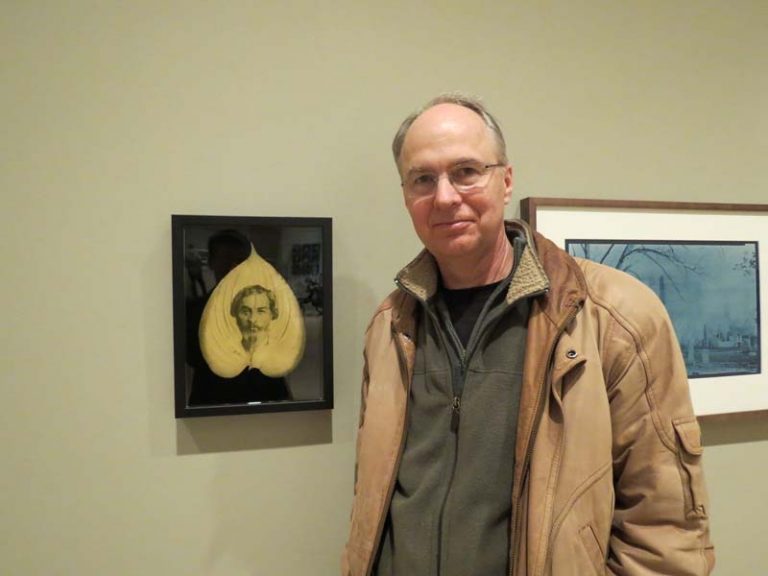

Juxtaposition is a key organizing principle in the articulation of the exhibition’s themes. To evoke timeless dimensions of war, portraits of Civil War and Vietnam War soldiers alike are developed in leaves, and memorials to Afghanistan and Civil War dead both are rendered in daguerreotype photographs. Similarly, cyanotype prints of the Antietam battlefield are echoed in intimate cyanotypes portraits of living young people, their eyes closed in memory and reflection. Portraits of Whitman himself are rendered in leaves plucked from his own Camden House garden, just as portraits of young Civil War soldiers are rendered in leaves from battlefield “witness trees” that stood in the 1860s. In short: faces, landscapes, and memorials from across time are juxtaposed in evocative media to assert connections.

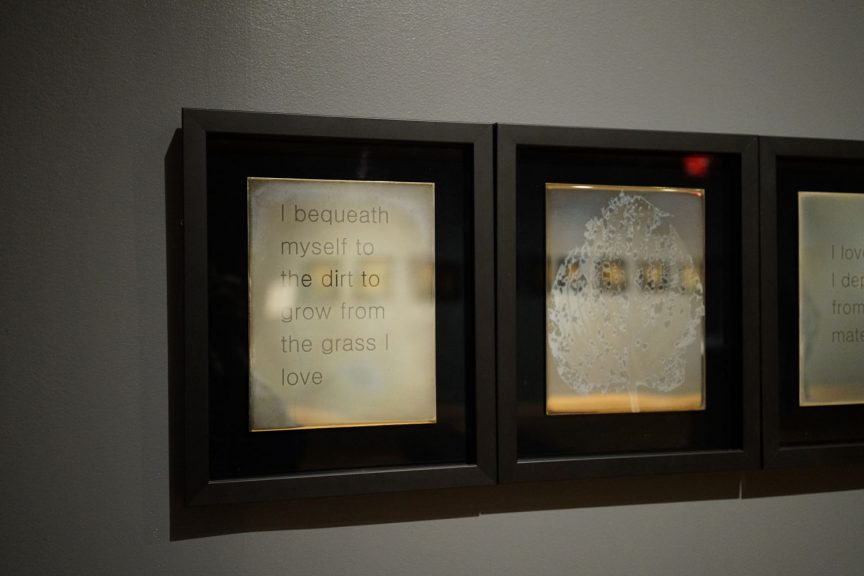

Leafprint portraits of Vietnam and Civil War casualties make physically tangible Whitman’s central trope—the leaves of grass as “hints” of the dead—and Schultz’s poems use the circular movement of traditional forms (the villanelle, sestina, pantoum, etc.) to enact cycles of natural and historical recurrence. Danh’s daguerreotypes and cyanotypes echo the work of Matthew Brady, Alexander Gardner, Timothy O’Sullivan, and other Civil War photographers, invoking historical perspectives as they render contemporary scenes and living “witness trees.”

The Liljenquist Civil War portraits have been celebrated in a special Library of Congress exhibition, have been featured on the covers of national magazines, and were used to striking effect in the recent PBS American Experience program, “Death and the Civil War,” based on the book, This Republic of Suffering, by Harvard President Drew Gilpin Faust. Now, in War Memoranda, these haunting portraits are developed in the flesh of leaves, some of them plucked from plants growing from the fields of Manassas, Sharpsburg, Gettysburg, or Appomattox. In “Song of Myself,” Whitman’s leaves of grass were “the beautiful uncut hair of graves . . . dark to come from under the faint red roofs of mouths,” and in War Memoranda long-gone faces confront us again in nature’s renewals.

For Whitman, the land itself is a revivifying memorial. In his poem “This Compost” he wonders at the purifying power of the earth that takes in death and sends back life, as when “[t]he resurrection of the wheat appears with pale visage out of its graves.” Correspondingly, the leaves that hold the soldiers’ images in War Memoranda have grown out of contemporary American soil and fulfill Whitman’s prediction that the war dead will inhabit “every future grain of wheat and ear of corn.” This is scientifically true, metaphorically arresting, and spiritually challenging. Pursuing intimate history, War Memoranda contemplates American wars and choreographs moments of encounter with our national past and the people who lived it.

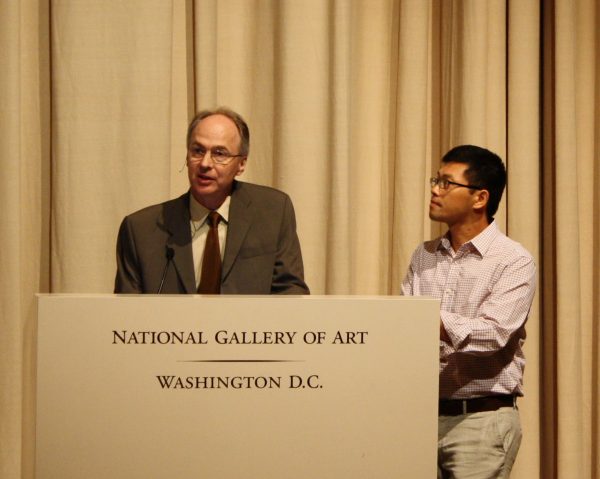

Robert Schultz and Binh Danh

I contacted Binh, asked questions, received a generous response, and a collaboration began. At my urging he began reading Walt Whitman (What is the grass?…the beautiful uncut hair of graves…) and, in turn, he instructed me in the art of chlorophyll printing. Later, when he came to Virginia for residencies at Hollins University and Washington & Lee University, we were able to work together in person.

My interest in Whitman and Binh’s in early photographic techniques converged at the U.S. Civil War, and we’ve driven together to battlefield sites in Virginia, Maryland, and Pennsylvania, taking photographs, doing research, collecting leaves from “witness trees.” Along the way, we hatched the idea of a joint exhibition. He concentrated on daguerreotype and cyanotype photography and generously taught me his chlorophyll print process and assigned to me the project of making leafprints of Whitman portraits and the Civil War photos in the remarkable Liljenquist Family Collection at the Library of Congress.

War memorials are too often mute, naming the dead with fitting solemnity but neglecting to say anything of what the dead know. The cenotaph, the column, the mounted soldier—such monuments stand for the soldierly virtues of courage and sacrifice but say little of how courage differs between men and what exactly each has sacrificed. Perhaps of all our national monuments, only the Vietnam Veterans Memorial gives the civilian a shiver of understanding. "We wade on in", Schultz writes of the Memorial, as if we were not on the Mall in Washington but in the swamps of southeast Asia, a place where "men and women hold each other, mortal, drowning." Faced with Maya Lin’s austere granite gash, "particular deaths rush out". It is impossible not to be moved under such an assault, not to feel in some small but significant way involved.

– Molly Rogers, “Stricken,” author of Delia’s Tears